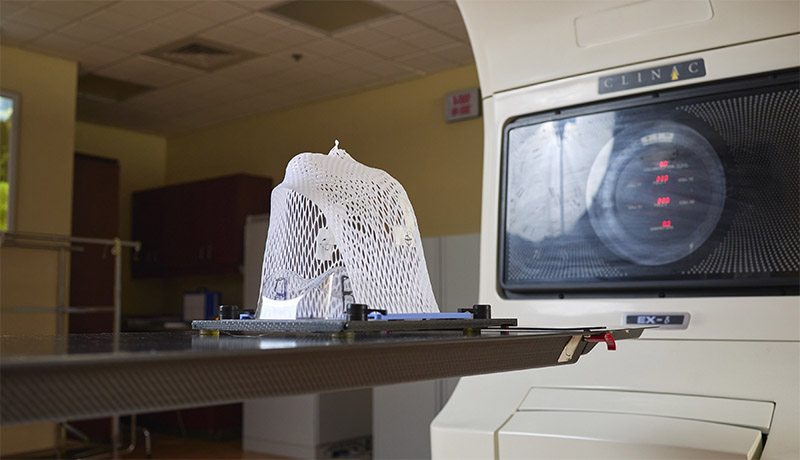

A patient lies nervously on their back, their head secured inside a helmet of sorts that is designed to hold it perfectly still.

Finally, the patient is moved into the device so their head is inside it. The medical team leaves the room to go to a control center where they will carry out the task at hand: destroying a malignant brain tumor through the use of a device known as a linear accelerator.

Such devices have been game changers in brain-related treatments, as they focus several beams of radiation—each too weak to damage cells on its own—onto a targeted area, helping improve outcomes and patient experiences.

There’s no incision, no general anesthesia required, and patients can typically undergo treatments in an outpatient manner, meaning there’s no hospital stay.

A closeup of a form-fitting head guard that is used to keep patients still during their treatment.

Like other recent technological advancements, these devices are helping medical personnel gain some advantage in the fight against cancer, but they need trained professionals to operate them.

Those professionals—perhaps the most vital thing that the devices need to work—are something that UT’s Department of Nuclear Engineering is in an ever-growing position of strength to provide, thanks to a relatively new program with origins dating back about a decade.

“We’ve had some related courses for students for a while now, but we formally launched a program in medical physics in 2019, giving them an opportunity to earn a master’s degree and gain practical experience while doing so,” said Wes Hines, department head, Postelle Professor, and Chancellor’s Professor. “We were hoping for a good response, but it has garnered interest well beyond our highest expectations.”

The original goal was to have perhaps six new students enroll in the program each fall. In reality, 18 students have enrolled in the first two years, attesting to the attraction that the program has for students.

To be prepared to use their expertise in the real world, students need to be able to practice using the equipment—and that experience is a key component. One thing that sets the program apart is that the two people most responsible for carrying out the coursework are themselves professionals in the medical physics field.

Michael Howard, the program’s director, and Chet Ramsey help lead the medical physics courses, bringing with them years of expertise from Tennova and Covenant Health, respectively. Together they translate their experiences into lessons and play a vital role in helping students gain the skills that can be learned only in a clinical setting.

As proud alumni of the Tickle College of Engineering, both have given their time and efforts to creating the program with a sense of serving humanity as a driving force.

“We are super excited about this program because medical physicists are an integral part of the oncology field, which continues to grow in importance,” said Howard. “Getting the students involved is vital to training them to be professionals in the field, whether it be behind the scenes of research and development, actually treating patients, or working with diagnostic imaging to help diagnose patients. We have a wealth of faculty, not only academic but clinical as well.”

Annette Robbins and Michael Howard.

Ramsey explained that to become a medical physicist requires completion of an accredited course of study and a two-year residency, much like other careers in medical fields.

The Commission on Accreditation of Medical Physics Education Programs gave its approval to UT’s program in 2019, making it one of just 60 accredited programs in the US and Canada.

While there is a demonstrated growing need for professionals in the field, the rigorous process and relatively small numbers of accredited educational programs have led to a situation where demand far exceeds supply.

For programs like UT’s, that means there’s no shortage of interested students, allowing the department to be selective while also filling a national need.

“You have to have a degree from one of these accredited degree programs and then you have to complete a two-year residency in either diagnostic imaging or radiation therapy before you’re allowed to sit for your board exam,” said Ramsey. “So in addition to the training students get in the classroom, our program connects them with residencies at places like Covenant, Tennova, UT Medical Center, and Provision, allowing them to take clinical rotations and complete that crucial step.”

Howard points out that the experiential requirement is so important that it was a part of the discussions on how to build out the program from the very start.

It also led to them placing a soft cap on the number of students that they admitted to the program in a given year, so that they could be certain that anyone who came for the courses could also meet the clinical experience requirement when applying for residencies.

“We didn’t want to build a program where students came, graduated, and couldn’t get into residencies, so that was something that was a key to our plans from the start,” said Howard. “In setting it up, we also determined that we wanted to try to limit each new class of students to 10 people, so that there would be plenty of hands-on training to go around.”

A close-up look at the internals of a linear accelerator.

Clinical experience also gives students the chance to learn and research the latest technologies in the field, something Ramsey said would also make the students attractive candidates for residencies that lead to eventual certification.

“It’s a highly in-demand job right now and will only get bigger,” he said. “But even within that, our students will stand out because of their experiences and exposure to different machines and techniques. If you have two candidates that are otherwise equal but one has experience with performing task A and the other can perform tasks A, B, C, and D, it obviously elevates them. And that’s what we’re doing for our graduates.”

One of the concerns they had for the new program was that students might be hesitant to come since there wasn’t a long history of successes.

Their successes so far have allayed those fears. A steady stream of inquires has continued to come in, reflecting the desire for the program in general and the early success that the department has had with it.

Those accomplishments, ultimately, will help improve the lives of millions of people stricken with cancer.

“Pretty much everyone in the world has been touched by cancer—whether they had it themselves or a friend, or a loved one, or a coworker had it,” said Howard. “When you can train students that can go out and help fight cancer, help change lives, it’s its own reward.”

One student at a time.