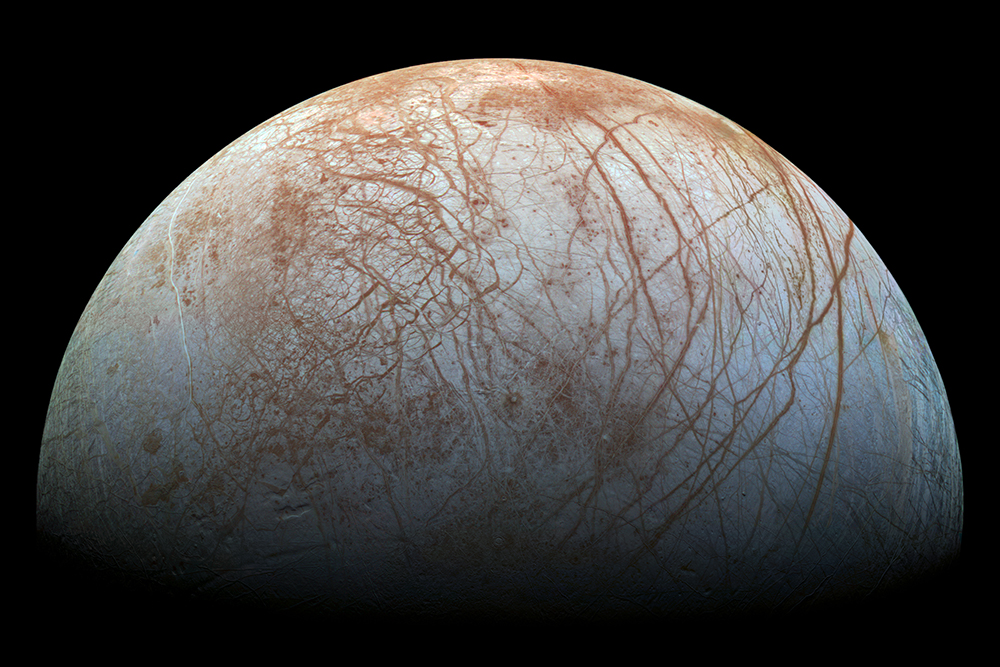

Photo courtesy of NASA. This image of Europa shows color variations across the surface. Areas that appear blue or white contain relatively pure water ice.

Jamie Porter Blazes Trails into Space Exploration

As a young girl, Jamie Porter loved math but hated science. Biology and chemistry had too much memorization in the beginning, which repelled her.

“That’s just not how I learn,” she recalled.

Now she gets to have the best of both worlds as an assistant group supervisor for the Space Environmental Effects Engineering team at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) working on NASA missions like the Europa Clipper, which is a mission to a moon of Jupiter that is thought to have liquid water.

Porter came to UT knowing she wanted to be an engineer, but she majored in electrical engineering before a presentation about nuclear engineering in Engineering Fundamentals piqued her curiosity.

“My mom was like, ‘but you hate science,’” laughed Porter. “But the science isn’t bad. Space radiation is a mix of astronomy, general physics, and engineering. It’s more fun for my brain.”

A Knoxville native, Porter graduated from UT with a bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD from the Department of Nuclear Engineering, spending a total of 12 years in the program. Although she didn’t realize it at the time, she made history as the first African American woman to graduate from the department.

“In 2012, we thought I might be the first, but we didn’t know if it was something to be proud of or embarrassed by,” she said. “I found out later that I was probably only the second African American woman to graduate with a PhD from any nuclear engineering program in the US.”

Whenever Porter can pay it forward, she does. She didn’t set out to be a trailblazer, but she has since taken the role of mentor to heart and accepts invitations to speak to minorities in the program and has spoken at commencement to the entire department twice.

Two of her younger colleagues at APL were also the first African American females to graduate from nuclear engineering programs at their respective universities, and Porter offers them mentorship too.

“They haven’t been there as long, I want them to understand their place and their wealth,” she said.

Jamie Porter stands in front of the new Zeanah Engineering Complex still under construction, future home of the Department of Nuclear Engineering.

More than any other person, Professor Emeritus Lawrence Townsend was integral to getting her interested in space. It was his mentorship that opened the door for her own curiosity in space radiation, as he was the only faculty member in the department at the time with a connection to NASA.

She got a job working as a summer research intern for him, and then later he became her graduate professor and she eventually did her postdoc with him.

“He’s like my work dad,” she said. “He’s seen me when I was eighteen, when I was engaged, when I got married, and then when I had kids. I don’t think I would have gone to graduate school if I didn’t do that freshmen research with him and stay with him that whole time.”

Once she started down the path of space radiation, she never turned back.

“It has nothing to do with power plants,” she joked.

Curiosity is what led Porter into the world of radiation, and curiosity is still at the heart of her work.

—Jamie Porter

At APL, she works closely with materials science engineers, astronomers, electrical engineers, etc. One of the tasks of her team is to figure out what missions need to build spacecraft that can withstand and perform properly in radiation environments other than here on the ground.

What she has learned is that there’s no training for what she does, so she has to use her curiosity and training to continue learning.

“Europa Clipper is one of the worst electron environments we’ve ever seen,” she said. “It’s horrible for radiation. It’s high dose, it’s electron dominated, stuff is sparking. We’re in charge of telling them how to keep these things from dying.”

Porter says that studying other planets offers questions that can help us earthlings. Questions like, Did these planets used to be like earth? What’s there? What used to be there? What happened to them?

“When I think about space and a mission like Europa Clipper, it’s exciting because we know there is water there,” she said, noting that where there is water, there is the likelihood of life. “There is a very high probability that there is life on Europa, even tiny organisms, that makes it worthwhile to keep exploring. Maybe we can even find something that can help us heal this planet.”